Poverty is a complex issue that is typically measured at the household level, taking into account the resources that are shared among multiple individuals. However, many existing studies rely solely on individual-level survey data to estimate poverty rates. This approach can lead to inaccurate estimates, particularly in cases where individuals within a household have differing levels of access to resources.

The use of administrative data is a promising approach to measuring poverty, as it provides a wealth of information on individual addresses. By aggregating information across individuals who are more likely to belong to the same household, we can develop more accurate estimates of poverty and better understand the ways in which poverty affects families and communities.

In our 2022 Data Science for Social Good (DSSG) project, we used the Washington Merged Longitudinal Administrative Dataset (WMLAD) to predict household groupings in the Washington State. This database merges administrative data from various state agencies including the Employment Security Department (ESD), Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS), Department of Health (DOH), Secretary of State, Department of Licensing (DOL), and WA State Patrol, covering the period from 2010 to 2017. Each time an individual interacts with any of these agencies, they are assigned an anonymized address code, which is further augmented by an imputation algorithm developed by previous WMLAD users (more details here).

In this blog post, I will introduce a longitudinal approach that I proposed for our team to improve the imputed addresses and construct more reliable household groupings. Don’t forget to also check out our presentation and media coverage :)

Motivation

To assess whether and how these imputed addresses can be improved, I started by comparing the distribution of households based on naive co-residences derived from WMLAD and the census data from April 2010. Upon exploratory data analysis, I observed a significant overestimation of one-person residences, with WMLAD indicating 38% household groupings compared to only 27% in the census data. Consequently, my next step was to identify which led to the overestimation of one-person residences using naive co-residences.

Following an extensive literature search and consultation with various stakeholders, I identified three potential scenarios that contributed to the overestimation of one-person residences. I presented my findings to the team, along with potential solutions to address these scenarios.

Scenario 1: Lack of interactions

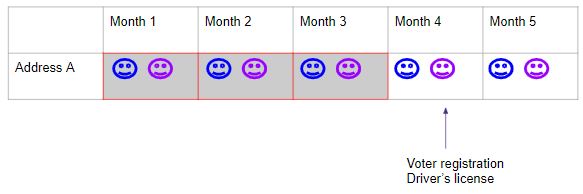

This occurs when certain household members, especially children, have less interactions with government agencies than adults, resulting in fewer recorded addresses for imputation. For example, addresses for children may only be recorded when they register to vote or obtain a driver’s license, which implies that the observation of some one-person residences may simply be due to the absence of their children in previous records.

To address this circumstance, I recommended adjusting certain one-person residences to reflect their actual co-residence with children. For example, in the scenario illustrated below, a child (purple face) began to co-reside with others (blue face) in month 4, while the address records showing only one person living at that address previously. In such cases, we need to reflect their co-residence accurately.

Scenario 2: Imputation error

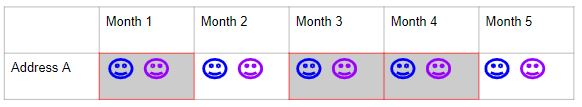

Another pattern that drew my attention was frequent movements into and out of the same place, which may indicate an imputation error.

A plausible fix was in cases where we observe a person living alone and co-residing with others alternately at the same address, we could adjust the one-person residences to reflect the nearest co-residence that the individual belongs to.

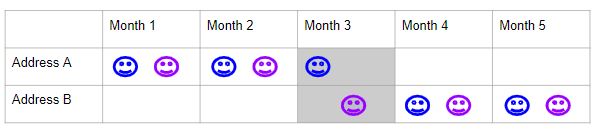

Scenario 3: Move in and out

The third scenario is more complex. One-person residences may occur during a transition period when a multi-person residence moves out simultaneously to a new location, but their addresses are not updated accordingly.

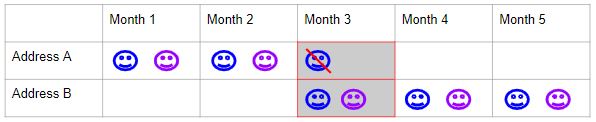

In cases where we observe distinct co-residence members before and after a one-person residence at a particular address, and the prior co-residence appears again in the future, we adjust the one-person residence to reflect the subsequent co-residence. As depicted in the illustration below, we should only modify one-person residences in month 3 when the co-residence composition in month 2 and month 4 matches.

Modifying one-person residences that fall under these scenarios did not conclude the analysis, as it could result in duplicates where a person appears at multiple addresses during the same time period. Therefore, we should eliminate duplicates based on recorded addresses, rather than imputed ones, which provide a more reliable indication of the address that the person belongs to.

How effective is this algorithm? After implementing the modifications, the percentage of one-person residences decreased from 38% to 31%, bringing it much closer to the census record of 27%. We are currently developing a methodology paper that details this approach along with more real-world data applications. We anticipate that our methodology and resulting household groupings will be beneficial in addressing significant policy questions.